Voters in the world's most populous Muslim-majority country will elect a new president and parliament on February 14. It will mark the first change of leadership in a decade.

Indonesia elections: What you need to know

DWNews || Shining BD

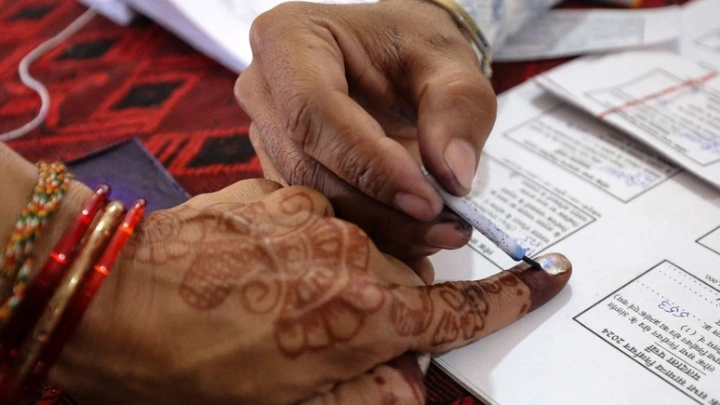

Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim-majority nation, is holding elections on February 14 in which people will cast their ballots to elect not only a new president and vice president but also members of parliament and local legislative bodies.

The election is a massive undertaking, with over 204 million of the country's 270 million people registering to vote across an archipelago made up of some 17,000 islands. The voters are spread across three time zones, from Papua in the east to the tip of Sumatra over 5,000 kilometers (3,000 miles) away in the west.

Young people make up the majority of the registered voters, with some 55% of them aged between 17 and 40, according to the General Elections Commission.

Incumbent President Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, is finishing his second term in office and cannot run again because of term limits.

This year's vote will thus lead to the first change in leadership in a decade.

Who are the presidential candidates?

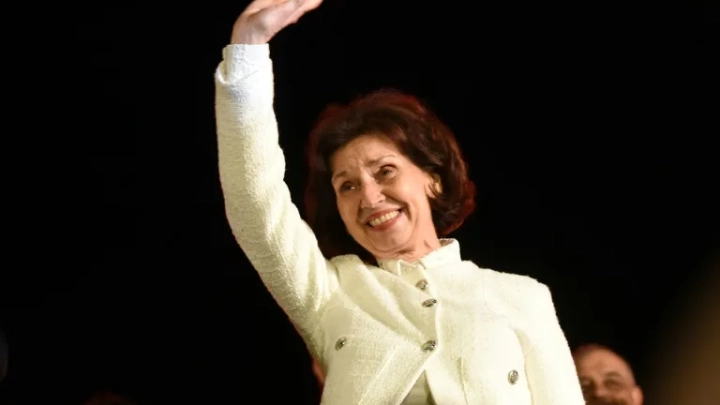

Three candidates are vying to succeed Jokowi as president: Ganjar Pranowo and Anies Baswedan, both former governors in their 50s, and Prabowo Subianto, the current defense minister.

Subianto is a 72-year-old former army special forces commander who is running for the top job for a third time. He lost to Jokowi in 2014 and 2019.

To cement his chances this time round, Subianto has roped in the hugely popular president's son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as his running mate for vice president.

The candidacy of 36-year-old Raka, who is half Subianto's age and currently serving as mayor in Surakarta city, is seen by many analysts as an attempt to secure more votes from the younger generation.

Subianto also hails from an elite political family. He was once the son-in-law of Suharto, a military dictator who was ousted from power in 1998 after over three decades of rule.

Subianto is accused of rights abuses while serving as a military chief during the dying days of the Suharto dictatorship. The allegations are unproven, and Prabowo has always denied any responsibility.

Ganjar Pranowo, another candidate, is a former governor of Central Java Province.

His presidential bid is backed by the country's ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P).

Pranowo has announced incumbent Cabinet minister Mahfud Md as his running mate.

Pranowo adopted the political style of President Widodo by trying to gain sympathy from grassroots movements.

The third presidential hopeful is Anies Baswedan, former governor of the Indonesian capital, Jakarta. His running mate is Muhaimin Iskandar, leader of the Islamic National Awakening Party (PKB) — one of the most powerful Islamic parties in the country.

In 2017, Baswedan ran for governor of Jakarta against Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, who is of Chinese heritage. Baswedan won the election — while his competitor was sentenced two years in prison for blaspheming the Quran during one of his campaigns.

According to latest surveys by Litbang Kompas, an independent research organization, Subianto is enjoying a considerable lead over the other two candidates, with about 39% of voters polled backing him compared to 18% for Pranowo and around 16% for Baswedan.

What are the key issues?

All three presidential hopefuls have made similar pledges on inclusive growth and welfare.

Jokowi's decade in office is generally seen as one of stability and growth for Southeast Asia's biggest economy.

And the three contenders have pledged to continue most of his initiatives, including boosting mining, expanding social welfare and continuing work on building a $32 billion (€29.7 billion) new capital city.

The candidates have set ambitious economic expansion targets and pledged to create millions of jobs, without giving out specific details as to how they will reach these objectives.

Who can vote and when can we expect results?

All Indonesian citizens who are 17 or older can vote.

Following decades of authoritarian rule, Indonesia embraced democracy in 1998 and adopted a national philosophy of equality and national unity called Pancasila, which is enshrined in the country's constitution.

Despite being the world's largest Muslim-majority country, it is constitutionally a secular state with a separation of religion and state. Nevertheless, political parties often employ religion in their campaign tactics.

The nation's parliament plays a relatively subordinate role in decision-making, with policy-making power resting with the presidency.

Under Indonesia's election rules, presidential candidates need 50% of the overall vote and at least 20% of votes in each province to win the vote.

To enter parliament, political parties, for their part, need to secure 4% of the vote.

A preliminary result from the elections commission is likely to be announced on the evening of February 14.

The final official outcome could take as long as 35 days to be made public.

if no presidential contender gets over 50% of the votes, the contest goes to a second and final round between the top two in June.

The new president will be sworn in in October.

Komnas HAM, an independent human rights body, said there are 17 groups of people who are likely to face challenges when exercising their right to vote.

They include people with disabilities, LGBTQ communities, indigenous communities and religious minorities, among others.

In North Sumatra province, Komnas HAM found instances of discrimination against LGBTQ voters.

"People from the LGBTQ community felt increasingly insecure (to vote) because there was a statement from the regional leadership declaring Medan as an LGBTQ-free city," Pramono Ubaid Tanthowi, a Komnas HAM official, was quoted by local media outlet detik.com as saying.

Voting by people with disabilities is also likely to be low, said Kikin P. Tarigan of the Indonesian National Commission for Disabilities, pointing to inadequate efforts on the part of the election commission to register people with disabilities as voters.

"The lack of access and assistance hindered people with disabilities to be listed as eligible voters," - Tarigan

Shining BD