Japanese filmmaker Nagisa Oshima's perspective on Bangabandhu

DailyStar || Shining BD

The 1971 Liberation War is the most significant event in Bangladesh's national history. Regardless of their age, sex, class, religion, caste, or ethnicity, millions of people in this country took part in the brutal conflict. The international media in general and many documentary filmmakers visited this country during the war. The images of the Bangladeshis' fierce resistance in the war were frequently overshadowed by the tragic scenes of them being tortured, raped, robbed, and killed by the Pakistani army in Western media and films.

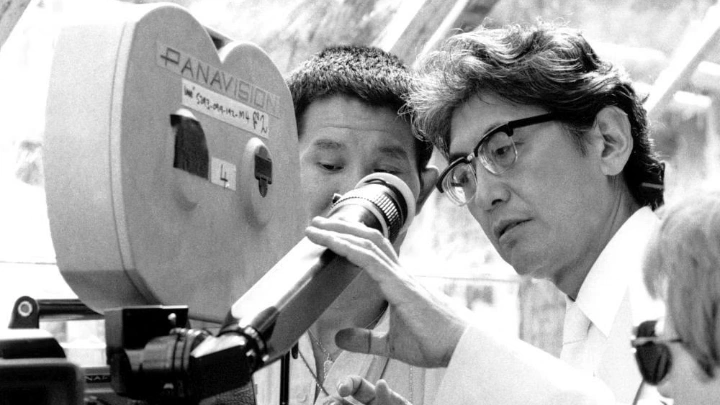

The obvious exception is Japanese director Nagisa Oshima. Nagisa Oshima is primarily recognized for the New Wave movement in cinema, and he frequently depicts disobedient and disadvantaged youths in his works. It's interesting to note how different his two documentaries about Bangladesh, Rahman: Father of Bengal (1973) and Joi Bangla (1972), are from the usual subjects of his movies. In his film Rahman: Father of Bengal, he captures the intense glory of Bangladesh's accomplishments in the years 1972–1973, despite the fact that the nation was still in a war-torn state after the conflict.

The nation had just attained independence. Homeward bound was Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Although the people of this nation were successful in gaining independence, a state associated with the memories of war, sadness, and uncertainty about the future persisted.

People frequently ask Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman questions like, "What does the country's leader think about his nation in such a turbulent time, how will he lead the country to move forward, how does the past give him incentives, and how will he be acted as the father both in the family and state life?"

In addition, issues such as Bangabandhu's political activities, favorite books, opinions on Bengali nationalism, marriage, family life, how his family suffered Pakistani violence during the war, and his visions and dreams for the nation are also discussed in this documentary in a conversational manner between the film director and Bangabandhu.

Although Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is the main subject of the documentary Rahman: Father of Bengal, Nagisa Oshima's opening sequence shows the Bengali waterways. Using voice-over narration, local music, folk songs, and pictures of people traveling on the waterways, he depicts the riverine landscape of this country.

He travels by steamer as well. Bangabandhu's birthplace, Tungipara, is the final stop on Oshima's water journey, and it takes him one day and one night to get there from Dhaka. The cost of a steamer is Tk 4, which is equivalent to 160 Yen in Japanese currency, while the daily wage of a common laborer is Tk 3 taka, which is equivalent to 120 Yen; such a topic also appears in his narration, which depicts Bangladesh in the years 1972–1973 in its historical context. The steamer passengers, including two children standing in the arms of a veiled mother, as well as some regular people praying in the late afternoon, were among the various scenes that slowly began to emerge. Other scenes included the crowd of people standing in piles on the steamer and small and large boats floating on the riverbed.

Although religious sentiments are deeply ingrained in the minds of the people in this region, the voice-over narration emphasizes that the country's constitution is founded on secularism. Following these scenes, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his councilors are seen praying at the dedication of a memorial tower for war dead, laying wreaths on the tower following the prayers, and concluding Bangabandhu's speech at a public gathering with the phrase "Joy Bangla."

As a result, Oshima initially represents the people's leader as the embodiment of the people's way of life—a way of life that draws on both religious conviction and the potent impulse of secular Bengali nationalism.

Then Oshima describes a historical occurrence: the 16th of December 1972. This past weekend marked the first anniversary of Bangladesh's Victory Day.

The new constitution is being sworn in as Prime Minister by President Abu Sayeed Chowdhury and Bangabandhu. Then we witness Bangabandhu's interview for the first time. He talks about Russell, his youngest child, and how his parents were assaulted by Pakistanis during the war. Again, the scene is altered. On the steamer, we see Oshima sailing in the direction of Tungipara. His camera records the captivating riverside scenery with a folk song playing in the background. The narration continues to establish a storytelling mode. In this way, the documentary alternates between segments that follow Bangabandhu on his journey to Oshima and others that feature interviews with him about his activities both inside and outside of his home.

This documentary's filmmaking style tends not to produce neat, manufactured forms. Including scenes and interviews with narration from an unobserved commentator gives conventional documentaries a semblance of reality. Oshima, on the other hand, wants to make it clear that this reality is also a construction. In some scenes, particularly when interviewing Bangabandhu, the positioning of Nagisa Oshima and the interpreter on the left side of the frame (with a partial back view) indicates a way to depict the process of filming in line with the features of "Direct Cinema."

The documentary film genre known as "direct cinema" first appeared in the 1960s in North America and the Canadian province of Quebec, providing independent filmmakers with an unstoppable incentive to make realistic movies for little money. It stays away from the use of imposed or hidden background voices or sound effects. The absence of studios, the use of synchronized sound, the operation of a lightweight camera by placing it on the shoulders rather than a tripod, and the use of lightweight cameras and technical equipment are some characteristics of these movies. Some elements of direct cinema can also be found in Rahman: Father of Bengal.

This documentary was primarily shot with a hand-held camera. In many instances, the camera is shaky and captures the incident as it really happened rather than taking a crisp picture. For this reason, the camera is strewn in various directions in many scenes of this movie, especially towards the end when capturing the public meeting scene to capture the flow of the crowd.

These images were captured by a hand-held camera, and many documentarian filmmakers may consider them to be N.G. (not good) shots. However, these scenes are depicted in the movie in a wholly artistic manner, adhering to the direct cinematic characteristic for understanding reality.

Bangabandhu taking the oath of office as prime minister, a typical depiction of Bangabandhu and his family's everyday home life at the breakfast table, his conversation with common people, Bangabandhu's spontaneous speech in front of hundreds of thousands of people of various classes and professions in several public meetings, and Bangabandhu's unique attachment to his seven-year-old son, Russell, are just a few of the important topics of Bangladesh's history that are

The clarity of Bangabandhu's political beliefs and self-described conversational style in responding to numerous questions, ranging from basic to crucial political questions, also become apparent at the same time. The documentary depicts a run-down primary school in Tungipara where Bangabandhu attended classes, the fact that Pakistani troops destroyed his ancestral home in 1971, a scene of his father Sheikh Lutfur Rahman praying in a makeshift and unremarkable home in Tungipara, and his father's desire to live in this village with his son and grandchildren.

We see the confident expression of this claim throughout the entire movie as Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur, an extraordinary man who came from a very ordinary home, will build Bangladesh. The past, present, and future of his [Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's] life are entirely dedicated to Bangladesh, it is stated in the movie's epilogue.

Indeed, Nagisa Oshima's words have been painfully recorded in history. Within two years of the production of this documentary, this great man who snatched freedom for Bangladesh was murdered here.

Being the Father of the Nation, he preserved the country by serving it until the very end of his life. He wanted to grant his own father's wish to live with him, but he was unable to return to his village.

Dr Fahmida Akhter - The writer is a Professor of Drama and Dramatics, Jahangirnagar University.

Shining BD