The next 50 days, while Iran prepares to elect a new President after the untimely death of Ebrahim Raisi, will be critical for Iranian politics

A dramatic change in Iran

Kabir Taneja, ORF || Shining BD

The untimely death of Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi, Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian, amongst others, in a helicopter crash in the country’s mountainous East Azerbaijan Province has sent shockwaves across the region. Raisi’s death was announced from Iran’s most revered Shia shrine, the mausoleum of Imam Reza, in Mashhad, his town of birth.

This unexpected but tectonic shift in Tehran’s politics comes at a precarious time, when the war in Gaza continues, tensions between Iran and Israel remain high, and Iran plays a critical role in a new iteration of ‘power block’ politics along with its partners in Russia and China. However, despite regional and international tensions around the ‘question’ of Iran, Raisi’s passing impacts Iranian polity much more than the Shia power’s regional policies.

Raisi’s death was announced from Iran’s most revered Shia shrine, the mausoleum of Imam Reza, in Mashhad, his town of birth.

For now, it is Vice President Mohammad Mokhber (who is also Iran’s Special Envoy for India) who is expected to hold the position of interim President until elections are held again within 50 days as mandated.

Succession

The now late president’s rise to power was not meteoric, but traditional and steady. Coming from a lineage of Islamic scholars, Raisi rose through the country’s judicial system, and paid his dues in cementing the Islamic Revolution’s ethos that has anchored Iranian ideology and polity since 1979. As noted scholar Arash Azizi pointed out, Raisi was the first president under Ayatollah Khamenei to offer unbridled loyalty to the Supreme Leader. By way of proving his mettle over the years, Raisi became the country’s eighth president in August 2021 at a time when the United States (US) had unceremoniously exited the nuclear deal, and the moderates in the country, led by then President Hassan Rouhani, were being institutionally sidelined.

In a rare act of public defiance, Rouhani released a letter last week, where he lamented the powerful Guardian Council highlighting him as unfit to defend his seat in the Assembly of Experts and alluded to a shrinking power circle controlled by the conservatives. Raisi’s passing will lead to a power struggle within Iranian circles. Accusations were ripe in 2021 that the elections were “rigged” in favour of Raisi’s candidature. Over the past few years, polling numbers have dropped drastically. In March, only 41 percent Iranians voted in the parliamentary and Assembly of Experts polls.

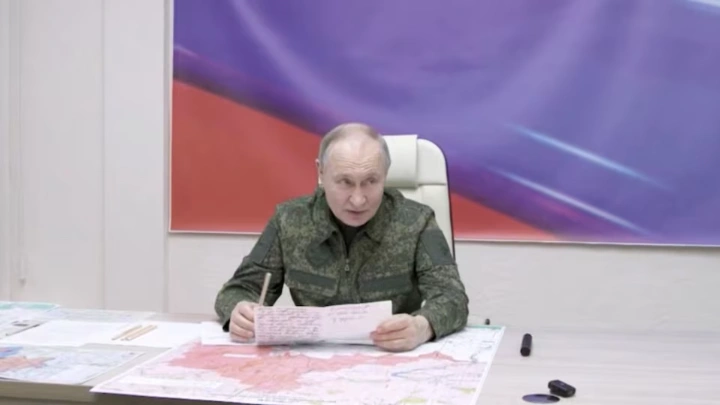

However, beyond electoral politics, there are bigger succession games afoot in the Islamic Republic. The all-powerful Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, where all bucks stop as far as the country’s policies, politics, and future is concerned, is in his late 80s. Raisi; along with the Ayatollah’s son, Mojtaba Khamenei; and another of Khamenei’s confidants, Alireza Arafi were in the running to become Supreme Leader themselves. Raisi’s impeccable ideological history and subservience to the Revolution and Ayatollah Khamenei, specifically during his time as the deputy prosecutor general in the mid 1980s, had him under the spotlight as a favourite. But Khamenei’s own succession is not reliant on his own whims and fancies. Scholar Afshon Ostovor highlights that Khamenei will need “buy-ins” from various power centres, including the The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), to make sure that whoever is the eventual choice is able to consolidate power with relative ease.

The all-powerful Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, where all bucks stop as far as the country’s policies, politics, and future is concerned, is in his late 80s.

However, moving forward, multiple power centres in Iran’s polity will pull and tug for influence. This may well include an outsize role by the IIRGC, which has gained tremendous power and momentum under Khamanei.

Fallouts

While Raisi was indeed the president of Iran, the country’s foreign and regional policies have been largely dictated by the Ayatollah, with the IRGC in the critical supporting role. The Revolutionary Guard, and its wings such as the Quds Force, has been responsible in developing what the Iranians now refer to the ‘Axis of Resistance’, a successful network of militias attached to Tehran allowing Iranians a significant level of culpable deniability. These include the likes of the Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Palestine, amongst other smaller entities in Iraq, Syria, and beyond.

Iran’s geostrategic designs may not see a wide or direct impact with a change of power in Tehran. The Ayatollah with the IRGC in tow calls the shots on most, if not all, such decisionmaking. The IRGC has not only strengthened itself immensely as a military entity, as defined by its role since it was set up in May 1979, but both politically and economically as well. It is also important to highlight here the division of military duties, where the Iranian Army’s job is to protect Iranian sovereignty, and the IRGC’s mandate is to protect the integrity and power of the Islamic Republic and the Ayatollah. For example, some of the Indian companies sanctioned by the US last month were faced with this reality based on the expectation that the components sold would be used by the IRGC’s expansive drones programme causing havoc not just across the Middle East, but Ukraine as well.

The IRGC has not only strengthened itself immensely as a military entity, as defined by its role since it was set up in May 1979, but both politically and economically as well.

Iranian support for the war in Gaza and Hamas, its incubation of Hezbollah, amongst other such policies, should be expected to go ahead without any major problems as Tehran reels from the loss of Raisi and moves to elect the next ‘Republic’ leadership. However, this leadership exists and functions under the Ayatollah and the IRGC’s supremacy, which shields it from any fundamental challenges to the structure of the state.

The next 50 days, regardless, will be critical for Iranian politics.

Shining BD