The same family has ruled Cambodia for nearly 40 years, and has dismantled opposition to its rule piece by piece. As Hun Manet continues in his father's footsteps, exiled Cambodian activists vow continued resistance.

What is left of Cambodia's political opposition?

DWnews || Shining BD

For nearly 40 years, the same family has led Cambodia without much threat to its rule. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet was sworn in last year, taking over from his father Hun Sen, who was in power from 1985 to 2023.

Hun Sen won another five-year term as prime minister in elections last July, but he quickly handed over the premiership to his son. However, 71-year-old Hun Sen remains a political force as the president of Cambodia's Senate.

Supporters of Hun Sen's long time in power contend he led Cambodia into modern times after the Cambodian genocide under the Khmer Rouge from 1975–1979, during which nearly 25% of the country's population perished.

But critics say Hun Sen ran Cambodia like a dictatorship, and cracked down on all political rivals, free independent media and was opposed to free and fair elections.

Time will tell whether Hun Manet will follow his father's strongman approach as prime minister, with some analysts expressing hope that he could be more of a reformer. However, Cambodia's political opposition has already been crushed in efforts to succeed Hun Sen.

"Unfortunately, the future looks bleak for Cambodia," Oren Samet, a PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkley, told DW.

"The opposition's electoral prospects, at least in the near term, appear slim," said Samet, whose research focuses on opposition parties and civil society.

"So far, Hun Sen is successfully navigating the tricky path of dynastic succession — which posed probably the biggest potential risk to his control this decade. If things continue smoothly on that front, it's hard to see how the opposition makes a dent from inside or outside," he added.

Cambodia's one-party political landscape

Hun Sen's Cambodian People's Party (CPP) has faced little challenge to its rule, with opposition parties being suppressed in recent years.

Prior to the 2023 elections, the Southeast Asian nation's electoral commission disqualified the main opposition Candlelight Party from running, allegedly over paperwork irregularities.

The elections in 2018 also saw the now-defunct opposition Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) banned from running.

But the crackdown didn't end there, as the party's former leader Kem Sokha was jailed for 27 years in 2023 over charges he conspired with foreign powers to overthrow the government.

And last year, Cambodia implemented a law that prevents individuals from running as political candidates in future elections if they do not vote.

Neil Loughlin, assistant professor in comparative politics at City, University of London, said there are few people left to oppose the long-reigning CPP.

"The CPP has effectively coerced the political opposition since 2017 and so far, Hun Sen, in anticipation of handing over power to his son, appears to have smoothed the hereditary succession by keeping key people inside the tent and well rewarded," he told DW.

"At the same time, the dismantling of the CNRP and then the Candlelight Party has left little in the way of meaningful, organized party opposition in the country," he added.

Launching a new pro-democracy movement?

With no political opponents inside Cambodia big enough to challenge the CPP, Cambodian political figures overseas have launched a new pro-democracy movement.

The Khmer Movement for Democracy (KMD), launched in March, and registered in the US state of Massachusetts, intends to serve as a de facto opposition to the CPP.

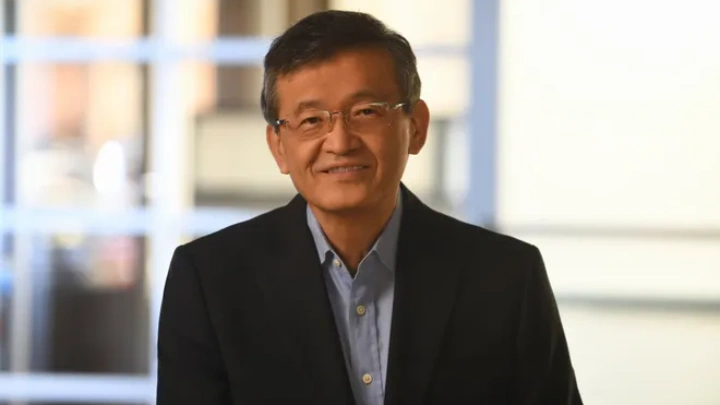

The movement is led by Noble Peace Prize nominee and exiled Cambodian, Mu Sochua, who aims to hold Hun Manet's regime to account and attract attention to the government's crackdown on political voices and activists both at home and abroad.

"The current state in Cambodia is one of fear and repression, where criticism of the government is met with severe and often brutal consequences. Today, the voice of the Cambodian people can only resonate through the global diaspora," Mu Sochua said in a press statement sent to DW.

Loughlin said Cambodians overseas are trying to maintain pressure on the ruling government.

"I think those opposed to the [government] are doing what they can from outside the country to keep the flames of opposition to the CPP alive," he said.

"The diaspora has always been an important component of that, providing financial support, and mustering international pressure on the Cambodian government when it breaks democratic norms or commits human rights abuses," he added.

Cambodia ranks second to last (141 out of 142) in the World Justice Project's global rankings for 2023. The rankings are based on several indicators, including human rights, social justice and the economy.

Can the new movement make a difference?

However, researcher Samet said it will be difficult for the KMD to influence reform in Cambodia while operating overseas.

"The KMD represents the latest iteration of efforts by Cambodia's opposition to retool and encourage international pressure on the Hun regime. It's not immediately clear that it will be any more successful than previous attempts," he said.

Samet added that it will be tough for the KMD to have an impact and draw attention to the cause of political pluralism in Cambodia, as policymakers are occupied with other conflicts and challenges to democracy.

"Making Cambodia stand out will be difficult … They can certainly make a lot of noise, and they are well positioned to reach policymakers in places like the US Congress," he said.

"The worst thing the Cambodian opposition could do would be to give up completely. Given the intensity of repression at home, it's understandable that many in the opposition are seeking to do this from overseas," Samet underlined.

However, Cambodian activists abroad still risk arrest if involved in political protests towards the CPP.

Earlier in March, several Cambodian activists were arrested in Thailand by authorities ahead of Hun Manet's official visit to Bangkok. Phil Robertson, Asia deputy director of Human Rights Watch, labeled the arrests as an example of "transnational repression" against Cambodian voices.

Shining BD